Joseph Husslein, S.J., and The American Catholic Literary Revival: “A University in Print”

By Stephen A. Werner*

(This article was previously published in Catholic Historical Review 87 (October 2001): 688-705.)

I. Rationale and Organization of “A University in Print”

Arnold Sparr described the American Catholic Literary Revival of this century in To Promote, Defend, and Redeem: the Catholic Literary Revival and the Cultural Transformation of American Catholicism, 1920-1960.1 Sparr mentioned the work and writings of such figures as Daniel A. Lord, Francis X. Talbot, and Frank O'Malley. Other Catholic writers also contributed to this revival, including Allen Tate and Joseph Husslein. Husslein is significant for his effort to promote Roman Catholic literature through his writings and more importantly through his project “A University in Print,” in which he edited over two hundred books on Catholic thought and culture for a wide audience.

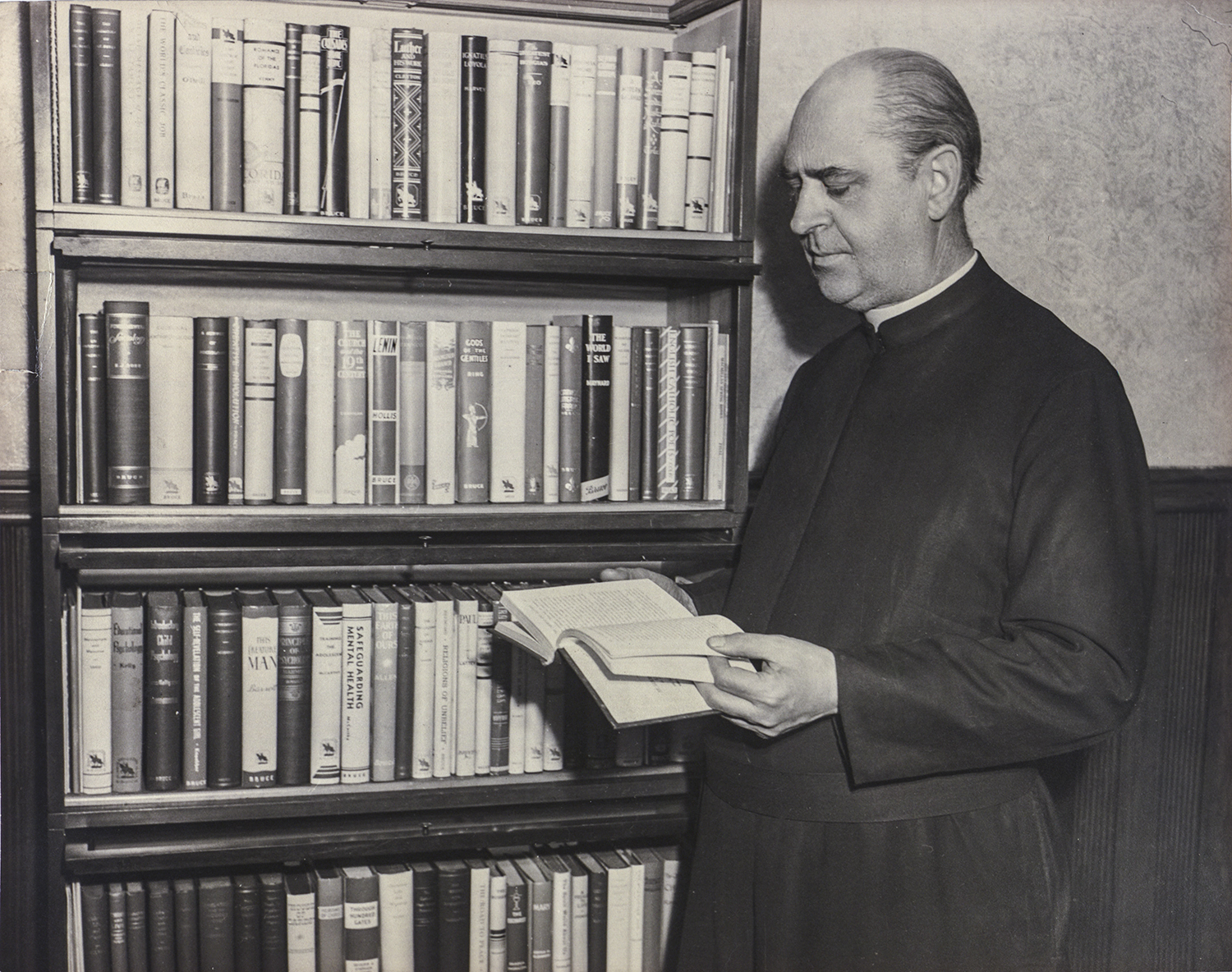

Joseph Caspar Husslein, S.J. (1873-1952), was born and raised in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. 2 In 1891 he entered the Society of Jesus at St. Stanislaus Seminary near St. Louis, Missouri. After studying and teaching at Saint Louis University, Husslein was ordained in 1905. From 1911 to 1930 Husslein worked on the staff of the Jesuit weekly America in New York and taught at Fordham University. During these years Husslein wrote over four hundred articles and ten books on such social issues as worker cooperatives, factory working conditions, woman workers, socialism, and unjust business practices. He produced one of the largest corpora of American Catholic writing on social issues. Husslein's most important books on social questions were The Church and Social Problems (1912), The World Problem: Capital, Labor and the Church (1918), Democratic Industry (1919), The Bible and Labor (1924), and The Christian Social Manifesto (1931).3 Of particular significance is Husslein's The Bible and Labor. In a method untypical for Catholic thinkers of this period, Husslein used the Bible--particularly the Old Testament--to develop principles for social ethics. This approach would not be repeated until after Vatican Council II.

In 1930 Husslein curtailed his writing on social issues and moved to Saint Louis University, where he founded the School of Social Service and began his “A University in Print.” 4 Husslein's work at Saint Louis University coincided with a particularly vibrant period for the university. New journals were published: The Modern Schoolman, Historical Bulletin, and Classical Bulletin. The Institute for Social Order was founded.

The figure from the University's Jesuit community to garner the most attention was Father Daniel Lord. A showman and promoter, he organized and ran the Catholic youth program Sodality. He edited The Queen's Work, produced musical pageants, and wrote hundreds of pamphlets. Lord and Husslein knew each other and believed they had the same mission of promoting Roman Catholicism, but Lord--flamboyant and gregarious--and Husslein--hardworking and quiet--were too independent for long-term co-operation. The St. Louis Jesuit community produced a number of “lone stars.” Husslein and Lord shared the American penchant for promotion.

For all the difficulties of the 1930's, it was an age of growing confidence for Catholics. The worst of the anti-Catholic nativism had died down; American Catholics had proven their patriotism in World War I; the National Catholic Welfare Conference brought some unity to the American hierarchy, and the calamity of the depression reaffirmed among Catholic social thinkers the conviction that Catholic teaching had much to say to the world. Radio provided a means for a number of speakers to disseminate a Catholic view. (It is unfortunate that Charles Coughlin is the most remembered of these voices.) The final and most important factor in the growth of confidence was simply the burgeoning Catholic population caused by large families descended from the immense waves of immigrants of the 1800's and early 1900's. Catholics had become the largest denomination in America. American Catholicism had the confidence not only to promote itself to the world, but ironically, and perhaps more importantly, Catholicism had to promote itself to its own members.

Husslein's “A University in Print” flowed from his social thought. He believed that society could only be restored with a return to religion and morality. Husslein believed that Catholic social teaching, especially Leo XIII's Rerum novarum, held the keys to rebuilding society. However, such a restoration required knowledge of Catholic thought and teaching. This required high-quality Catholic literature. Husslein desired to help energize Catholicism in America by promoting and disseminating Catholic literature and by promoting Catholic writers and thinkers. Yet Husslein did not want to limit his effort to religious writing. He believed that Catholic scholars had much to say on history, social science, and other subjects. He envisioned a wide range of topics for “A University in Print.”

In addition to responding to Husslein's social thought, “A University in Print” also responded to the lack of American Catholic intellectuals and the lack of American Catholic literature. In Husslein's time the shortage of American scholars was widely recognized. John A. O'Brien, Newman chaplain at the University of Illinois, published Catholics and Scholarship: A Symposium on the Development of Scholars (1939), a collection of papers lamenting the lack of Catholic scholarship. 5

Many Catholics lamented the lack of American Catholic literature. There was a deliberate effort to create and encourage an American Catholic literary revival. Arnold Sparr has seen three goals behind this effort: to promote American Catholicism, to defend the Catholic faith, and to redeem American secular society. Sparr described the American Catholic literary revival as a “curious mixture of insecurity, protest, and apostolic mission.” 6

Husslein had two markets. He wanted to expose non-Catholics to the best of Catholic writing and to reach Catholics, for he believed that many of the latter were unaware of their intellectual heritage. Husslein sought first “the constant perfecting of an intellectual and inspiring Catholic leadership; second, the acceptable interpretation of Catholicism to the non-Catholic intellectual world.” 7 Husslein wanted to provide Catholic writings of high quality for those both in and out of academic settings.

Early in his career Husslein lamented the dearth of Catholic literature. Ironically, socialist publishing gave him a vision of what Catholics might accomplish.

The large and comprehensive set of Socialist classics--if we may dignify them with this name--translated from all languages, is bound in uniform edition and sold at the lowest prices, while we, with all our years of experience and all the grand literature at our disposal, have not yet been able to issue one single, handy, attractive, inexpensive and carefully exclusive set of our own Catholic classics of the world, or even of those of our own language--invaluable as such an edition would be for the class-room and library.8

Husslein also stated:

As Catholics we have relied too exclusively on the immediate influence exercised within the walls of our churches and the priestly ministrations in the home. The time has come when natural prudence, whose demands can never be safely disregarded, calls for a wider apostolate. The facts we have quoted show the truth of Bishop Ketteler's famous saying, that were St. Paul living to-day he would be conducting a paper.9

In 1918 Husslein described the Catholic answer to “The Great Farm Problem”:

It is necessary, therefore, for every influential agriculturist, and for every pastor of souls, wherever the country spire lifts up its cross above the waving tree tops and the sound of the angelus floats over the golden fields, to second the efficacy of prayer and the Sacraments by the systematic introduction of Catholic literature into every home. . . . If Catholic literature does not reach the farmer, Socialistic and other objectionable literature certainly will.10

In 1917 Husslein published a manual on how to organize Catholics: The Catholic's Work in the World: A Practical Solution of Religious and Social Problems of To-day.11 After a chapter describing a plan to bring converts into the Church with a “Win My Chum Week,” Husslein included three chapters on the importance of the Catholic press. He labeled the irreligious press of his day as “A Modern Delila” while describing the Catholic Press as “A Debbora of Our Age” calling forth Barak to attack the hordes of Sisera. Husslein's chapter “The Speedometer” described a motivational poster for counting the number sold of subscriptions to Catholic magazines.

All of these factors--Husslein's social thought, the lack of Catholic intellectuals, the lack of Catholic literature, and the socialist example--led to the launching of “A University in Print.” Husslein followed a twofold strategy: to provide a forum to publish American Catholic authors and to make Americans aware of the Catholic literary heritage going back to the Middles Ages.

Husslein worked out a plan with Bruce Publishing of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, whereby Husslein would select and edit the books which Bruce would publish as the “Science and Culture Series.” In 1931 Husslein started his “Science and Culture Series” by publishing A Cheerful Ascetic by James J. Daly. A historian of Saint Louis University has written:

It was one of the first well-planned efforts at developing the Catholic Market. The first book was A Cheerful Ascetic by James J. Daly, S.J., of the Department of English of the University of Detroit. The reception of this work augured well for the entire series. Christopher Hollis' two books, Thomas More and Erasmus, Shane Leslie's The Oxford Movement, Hilaire Belloc's The Question and the Answer, Martin C. D'Arcy's Pain and the Providence of God, and Donald Attwater's The Catholic Eastern Churches soon gave the Science and Culture Series an international flavor.12

Within a year and a half the Cardinal Hayes Literature Committee stated:

The Science and Culture Series . . . has already given to the reading public a number of useful and pertinent volumes and enriched present-day Catholic literature with works of unexcelled eminence in their respective fields.13

Husslein desired a university in print with books of biography, history, literature, education, the natural sciences, art, architecture, psychology, philosophy, scripture, and religion. Most books contained a short preface by Husslein. He later explained:

It was to be a university for the people, a university for the men and women with intellectual interests, whether within college walls or outside of them, offering to all the best scientific and cultural thought of Catholic thinkers, scientists, and literary men. Each work was intended to be the result of original research while at the same time presenting larger and more familiar aspects of the subjects treated. It was to be popular, but without sacrificing scholarship. 14

What is envisioned throughout was in truth a University in Print, free, wide and open as the world itself to all who are eager for truth, religion and the things of mind and spirit. And all this for the one supreme purpose of developing and inspiring an intellectual Catholic leadership such as now the world needs to win it back to Christ.15

The faculty of “A University in Print” were notable Catholic authors; their books were lectures with the world as their student body. Although started in the Great Depression, the series grew rapidly with such authors as Hilaire Belloc, Donald Attwater, Christopher Hollis, Theodore Maynard, Eva J. Ross, Daniel Sargent, Padraic Gregory, Joseph Clayton, and Fulton J. Sheen. One hundred and sixty writers, including twenty-one women, contributed.

Some of Husslein's books were designed for the college text market. But more books were published for outside of class reading. Since Husslein believed his “University in Print” could provide an alternative for those who could not attend universities, the bulk of Husslein's books were written for those not at colleges and universities (the vast majority of Catholics).

A year and a half after starting the “Science and Culture Series,” Husslein added the “Science and Culture Texts” series. In May, 1934, Husslein started the “Religion and Culture” series with The Catholic Way in Education by William A. McGucken, S.J. Husslein envisioned, but never started, a fourth series of sixteen books on missiology: “The Church Universal Series.”16

The emblem of the “Science and Culture Series,” modeled after the statue of St. Louis at the St. Louis Art Museum, appeared on the binding and title page of most books.

The fitting emblem of the series is the heroic figure of the crusader king, St. Louis, mounted on his straining charger and holding aloft the sword reversed, its hilted handle changed into a cross, humanity's true sign of progress.17

The “Religion and Culture “series had its own emblem.

Avoiding unsolicited books, Husslein preferred to select topics and then choose expert authors based on their contribution to the field and their ability to write in good literary English. Husslein also invited qualified authors to suggest topics. For the sake of quality, Husslein gave writers as much time as they needed. He boasted:

Never has the Science and Culture Series sought popularity at any cost, but has always insisted upon the cultural worth of any contribution accepted by it. Nonetheless it firmly sets forth as its ideal an invariable popularity of treatment, consistent with scholarship and genuine originality.18 Husslein described the requirements for each book: . . . that it combines in an outstanding way scholarship, originality and popular presentation, while its subject itself is not too specialized to be of vital and actual interest to the generality of intelligent readers.19

Working without a secretary, Husslein edited 213 books during a twenty-one-year period.

Bruce set up a subscription plan offering a 20% discount. New books were sent to subscribers on a five-day permission. Subscribers had to buy six books a year. Each new book, usually issued on the tenth of each month, came with a “Science and Culture Series Forecast” describing the next book. The success of Husslein's project helped the Bruce company survive the Great Depression.20

Distributors sold the books in the United States, India, the Philippines, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, England, Ireland, Canada, and Italy. Husslein cited an assessment by the Irish writer and contributor to the series, Aodth [Hugh] de Blacam:

Thus, broadcasting from Dublin no later than September 28, 1934, Aodth de Blacam said: “I recommend this remarkable series for more than one reason. The first is that it will appeal particularly to most Irish readers as being almost the only series of its kind appearing in English that is written from what most of us regard as the orthodox point of view. . . . The Science and Culture Series should serve our purpose if we were asked to point to a really trustworthy example of American culture--of American scholarship, deep and sound. Here we find that long range of interest, that freshness of point of view, and yet that reverent attitude towards tradition which together make up the characteristics of American culture.”21

Husslein produced a body of Roman Catholic religious literature within the context of a broader collection of books. In addition, he provided an important forum for publishing books of the faculty of Saint Louis University and his fellow Jesuits. Husslein worked on “A University in Print” until his death. Unfortunately, he did not groom a successor, although the Jesuit historian William Barnaby Faherty was recommended for the task. “A University in Print” died with Husslein.

II. The Scope of “A University in Print”

Husslein saw “A University in Print” as part of the Catholic Literary Revival and included several books reflecting this self-consciousness: Calvert Alexander, The Catholic Literary Revival: Three Phases in its Development from 1845 to the Present (1935); Stephen James Meredith Brown and Thomas McDermott, A Survey of Catholic Literature (1945); Elbridge Colby, English Catholic Poets, Chaucer to Dryden (1936); and Michael Earls, Manuscripts and Memories: Chapters in Our Literary Tradition (1935). Regarding Katherine Bregy, From Dante to Jeanne d'Arc: Adventures in Medieval Life and Letters (1933) a New York Times review stated:

This pleasant and well-made little book of essays upon medievalism is written from the Roman viewpoint primarily for Catholic readers, but that is not to say that its charm and richness of subject are the exclusive property of any creed. Any one sensitive to romanticism and the flavor of the past will find its pages delightful.22

Several books described particular figures in Catholic literature: Terence Connolly, Francis Thompson: In His Paths: A Visit to Persons and Places Associated with the Poet (1944) and Gerald Walsh, Dante Alighieri: Citizen of Christendom (1946). Other works covered broader ranges of Catholic literature such as Constance Julian, Shadows Over English Literature (1944); Mary Keeler, Catholic Literary France from Verlaine to the Present Time (1938); Inez Specking, Literary Readings in English Prose (1935); and James J. Daly, A Cheerful Ascetic and Other Essays (1931). These books show Husslein's emphasis on acquainting American Catholics with their older European heritage. Other figures in the American Catholic Literary Revival were concerned with twentieth-century Catholic writers.

Although it was called the “Science and Culture Series,” only three books covered science: Victor Allen, This Earth of Ours (1939); James Macelwane, When the Earth Quakes (1947); and James Shannon, The Amazing Electron (1946). Two books dealt with art: Frank Brannach [Francis Edward Walsh], Church Architecture: Building for a Living Faith (1932), and Padraic Gregory, When Painting Was in Glory, 1280-1580 (1941).

For Husslein, a revival of Catholic literature had to deal with the most important Christian literary work: the New Testament. Husslein gave particular attention to books on scripture. (It is a common misconception that Catholic interest in the Bible began after Vatican Council II.) Husslein sought a middle ground between the technicalities of critical biblical studies and simple devotional works by providing books for the intelligent reader that presented academic research, such as The Gospel of Saint Mark: Presented in Greek Thought-units and Sense-lines With a Commentary by James A. Kleist (1936); The Memoirs of St. Peter, or the Gospel According to St. Mark (1932); and with Joseph Lilly, The New Testament: Rendered From the Original Greek with Explanatory Notes (1956). Other books on scripture included William Dowd, The Gospel Guide: A Practical Introduction to the Gospels (1932); C. Lattey, Paul (1939); George O'Neill, The Psalms and the Canticles of the Divine Office (1937); and The World's Classic: Job (1938). Particularly important and well-read was the two-volume translation of Ferdinand Prat, Jesus Christ: His Life, His Teaching and His Work (1950).

In addition to writings on scripture, another fourteen books covered theology. Of particular importance were Gerald Ellard, Christian Life and Worship: A Religion Text for Colleges (1933-34); Francis Mueller, Christ (1935); and Piotr Skarga, The Eucharist (1939). Other works included Hilaire Belloc, The Question and the Answer (1932); C. Lattey, Paul (1939); Emile Mersch, The Whole Christ: The Historical Development of the Doctrine of the Mystical Body in Scripture and Tradition (1938); and Bakewell Morrison, The Catholic Church and the Modern Mind (1933).

Another twelve works in “A University in Print” dealt with Catholic social teaching. These ran the gamut from Paul Martin, The Gospel in Action: The Third Order Secular of St. Francis and Christian Social Reform (1932); Albert Muntsch, The Church and Civilization (1936); John K. Ryan, Modern War and Basic Ethics (1933, 1940); Thurber Smith, The Unemployment Problem: A Catholic Solution from the Viewpoints of Ethics, History, and Social Science (1932); to Thomas Schwertner, The Rosary, A Social Remedy (1934, 1952). A Commonweal review by Virgil Michel described Henry Schumacher's, Social Message of the New Testament (1937):

Topical expositions go progressively from personality to family, property and wealth, the state and authority, on the basis of the true Christian concepts of the new creature, the kingdom of God, the fatherhood of God, the brotherhood of man, the whole scale of virtues emphasized in the New Testament--all with abundant textual quotations. Many pages are truly enlightening. . . . Without a deep biblical knowledge and without a sympathetic feeling for human needs and social ills, the book could not have been written.23

Twenty-four books dealt with Christian history including five by Donald Attwater: The Christian Churches of the East (1947, 1948); The Golden Book of Eastern Saints (1938); St. John Chrysostom: The Voice of God (1939); The Catholic Eastern Churches (1935); and The Dissident Eastern Churches (1937). Describing the last two, The Dublin Review stated: “Single volumes on so large a subject could hardly be more complete, and they supply a need which a number of people in England and America have felt for a long time.”24

Other historical works were M. W. Burke-Gaffney, Kepler and the Jesuits (1944); and four books by Joseph Clayton: Pope Innocent III and His Times (1941); The Protestant Reformation in Great Britain (1934); Saint Anselm: A Critical Biography (1933); and Luther and His Work (1937). Regarding Joseph Clayton's book on Luther a New York Times review described it as “a just and temperate view of Luther,” and “a valuable piece of work.”25 Hilaire Belloc's The Crusades: The World's Debate (1937) received the following New York Times review:

Mr. Belloc brings all this to life in a book of straight-forward narrative and exposition which rises every now and then to heights of beauty and dramatic visualization, which grows naturally from the soil of his own scholarship and insight, and beneath which the current of his own earnestness flows deep and strong.26

Two books reflected the Catholic reappraisal of the Middles Ages: Roy Cave and Herbert Coulson, A Source Book for Medieval Economic History (1936), and James J. Walsh, High Points of Medieval Culture (1937). Two dealt with the history of the American West: Mabel Farnum, The Seven Golden Cities (1943), and Gilbert Garraghan, Chapters in Frontier History: Research Studies in the Making of the West (1934).

The Catholic interest in the conversion of non-Catholics can be seen in several works, three of which are autobiographical descriptions of the movement to Catholicism: Herbert Cory, The Emancipation of a Freethinker (1941); Theodore Maynard, The World I Saw (1938, 1939); and Dorothy Wayman, Bite the Bullet (1948). One book told the stories of forty converts from Knute Rockne to Shane Leslie: Severin Lamping, Through Hundred Gates, by Noted Converts from Twenty-Two Lands (1939). These books would have been contemporary with Merton's The Seven Storey Mountain. Husslein had his own disbeliever turned Cistercian: Father Raymond, The Man Who Got Even with God: The Life of an American Trappist (1941), about a cowboy called “the Kentuckian” who joins the Abbey of Gethsemane. Two books on the Oxford Movement reflect the interest in converts:

Shane Leslie, The Oxford Movement, 1833-1933 (1933, 1935), and William Lamm, The Spiritual Legacy of Newman (1934). A review in America describes Leslie's book: Shane Leslie has probably written one of his finest pieces of prose in this history. On a vast canvas he has attempted, and with conspicuous success, to give a picture of the Oxford Movement with the lights and shades of its historic background. With both hands, as it were, he has dipped deep into the tone coloring of literary artistry, and slapped on his colors in a startlingly brilliant ensemble that makes the Movement stand out with an intense vividness.27

Although Husslein's series had the goal of promoting Roman Catholic faith, it still allowed for an honest and sympathetic look at world religions as seen in two works by George Cyril Ring: Religions of the Far East: Their History to the Present Day (1950), and Gods of the Gentiles: Non-Jewish Cultural Religions of Antiquity (1938), and in the five works by Donald Attwater on the Eastern Christian tradition.

Four books dealt with Catholic education: Francis Crowley, The Catholic High-School Principal: His Training, Experience, and Responsibilities (1935); Daniel Lord, Religion and Leadership (1933); and William McGucken, The Catholic Way in Education (1934-1937) and The Jesuits and Education: The Society's Teaching and Practice, Especially in Secondary Education in the United States (1932).

The series included two books in French and one in Spanish. These were to be used in foreign-language courses as readers with religious themes: Luis Coloma, Boy (1934); Lucille Franchere and Myrna Boyce, L'aurore de la Nouvelle France (1934), telling the adventures of French Jesuits in early America, and Mary St. Francis, Loutil, Edmund (1937).

Six books dealt with the threat of Communism including: Hamilton Fish, The Challenge of World Communism (1946); Christopher Hollis, Lenin (1938); Robert Ingrim, After Hitler, Stalin? (1946); and Edmund Walsh, Total Empire: The Roots and Progress of World Communism (1951).

Over two dozen book dealt with Christian saints and heroes. The long list included Albert the Great, Charles Borromeo, John Baptist de La Salle, Boniface, Bridget of Sweden, Gemma Galgani, Joan of Arc, Margaret Mary, Philip Neri, Pius V, Teresa of Avila, and Thérèse of Lisieux. Hugh De Blacam contributed Saint Patrick, Apostle of Ireland (1941), and The Saints of Ireland: The Life-Stories of SS. Brigid and Columcille (1942). Theodore Maynard added three works: Too Small a World: The Life of Francesca Cabrini (1945); Mystic in Motley: The Life of St. Philip Neri (1946); and A Fire Was Lighted: The Life of Rose Hawthorne (1948). These books were not merely pious saint stories as is seen in a Saturday Review of Literature review of Margaret Routledge Yeo's, The Greatest of the Borgias (1936):

What qualifies the historical value of this well-written biography is that it is written from the Catholic point of view, in a science and culture series edited by Joseph Husslein, S.J. That need not, however, interfere with one's pleasure in Mrs. Yeo's vivid descriptions, her excellent painting in of background, and her knowledge of the Italian Renaissance in all its blood and mysticism. . . . It is the book of a deft research student and of an author who can write with vividness and charm.28p>

Within the category of saints and heroes came several works on Jesuit figures: Robert North, The General Who Rebuilt the Jesuits (1944); a translation of Paul Dudon, St. Ignatius of Loyola (1949); Francis J. Corley and Robert J. Williams, Wings of Eagles: The Jesuit Saints and Blessed (1941); and Robert Harvey, Ignatius Loyola: A General in the Church Militant (1936). Other works on famous Jesuits described Peter Claver, John Francis Regis, and Father Tim Dempsey, famous for his work among the poor in St. Louis.

The single largest category was religious living or devotional. This included a translation of Chanoine Casimir Barthas, Our Lady of Light (1947); Hugh Blunt, Life With the Holy Ghost: Thoughts on the Gifts of the Holy Spirit (1945); The Quality of Mercy: Thoughts on the Works of Mercy (1945); The Heart Aflame: Thoughts on Devotion to the Sacred Heart (1947); translations of Alexandre Brou's Ignatian Methods of Prayer (1949) and The Ignatian Way to God (1952); and a translation of Leonard Lessius, My God and My All: Prayerful Remembrances of the Divine Attributes (1948).

Several works dealt with the Holy Family: Francis Filas, The Family for Families: Reflections on the Life of Jesus, Mary, and Joseph (1947); The Man Nearest to Christ: Nature and Historic Development of the Devotion to St. Joseph (1944); and Husslein's The Golden Years (1945).

Six books covered Latin America: Edwin Ryan, The Church in the South American Republics (1932); James Magner, Men of Mexico (1942); John White, Our Good Neighbor Hurdle (1943); Joseph Privitera, The Latin American Front (1945); Peter Dunne, A Padre Views South America (1945); John Bannon and Peter Dunne, Latin America, an Historical Survey (1947).

Four books covered history: a translation of Joaquin Arraras, Francisco Franco, the Times and the Man (1938-39); Daniel Sargent, Christopher Columbus (1941); Richard Pattee, This is Spain (1951); and Mariadas Ruthnaswamy, India from the Dawn: New Aspects of an Old Story (1949).

The series included twelve books on philosophy with Vernon Bourke's Augustine's Quest of Wisdom: Life and Philosophy of the Bishop of Hippo (1945) the most important. A reviewer wrote:

The width of Dr. Bourke's Augustinian scholarship is seen in this, that he takes up the Saint's thought on several topics in the passages where the primary discussions are found, not in those where they are conveniently gathered together. This gives a fresh vividness and clarity to many matters which the casual reader of a few of the writings has come across. The merit of the book is in part that of good selection, both of incidents for biographical treatment and of passages for analysis. The analyses are clear and never too heavily loaded. It is by means of them chiefly that the author opens St. Augustine's mind to the reader.29

Other works included Charles Bruehl, This Way Happiness. Ethics: The Science of the Good Life (1941); Louis Mercier, American Humanism and the New Age (1948); Thomas Neill, Makers of the Modern Mind (1949); four books by Henri Renard: The Philosophy of Being (1943); The Philosophy of God (1951); The Philosophy of Man (1948); and The Philosophy of Morality (1953) prefaced by Jacques Maritain; and Fulton Sheen, Philosophy of Science (1934). The Dublin Review described André Bremond's, Religions of Unbelief (1939) as “profoundly interesting, and very easy to read. [Bremond] deserves congratulations on the result.”30

Twelve books on psychology and psychiatry included Hubert Gruender, Experimental Psychology (1932); Francis Harmon, Principles of Psychology (1938, 1951, 1953) and Understanding Personality (1948); William Kelly, Educational Psychology (1933, 1945) and Introductory Child Psychology (1938); Charles McCarthy, Training the Adolescent (1934) and Safeguarding Mental Health (1937); and John Cavanagh and James McGoldrick, Fundamental Psychiatry (1953).

Nine books dealt with sociology and social work. Works of note included Charles McKenny, Moral Problems in Social Work (1951), and two works by Clement Mihanovich, Current Social Problems (1950) and Principles of Juvenile Delinquency (1950). Eva Ross provided three works in the early period of “A University in Print”: A Survey of Sociology (1932); Rudiments of Sociology (1934); and Fundamental Sociology (1939). A work from the later period is Nicholas Timasheff and Paul C. Facey, Sociology: An Introduction to Sociological Analysis (1949). These books on sociology were regularly reviewed by such journals as American Journal of Sociology, Sociological Analysis, Sociology and Social Research, and Social Forces. A review of James F. Walsh, Facing Your Social Situation (1946), in Sociology and Social Research states:

It is very well written and is successful in making the psychologic thought of real value to the student. There is ample evidence that the author has a scholarly grasp of the field. . . . The injection of Catholic theology into the subject matter has been accomplished with considerable tact and unobstrusiveness, although in several instances the author chides some social psychologists for their ignorance on certain religious and church matters. . . . The book is engagingly written too. . . . 31

Eight works dealt with living a devout Christian life: Martin D'Arcy, Pain and the Providence of God (1935); Marguerite Duportal, A Key to Happiness: The Art of Suffering (1944); and six works by Bakewell Morrison: Marriage (1934); Revelation and the Modern Mind: Teachings from the Life of Christ (1936); Character Formation in College (1938); In Touch with God: Prayer, Mass, and the Sacraments (1943); Personality and Successful Living (1945); and God Is Its Founder: A Textbook on Preparation for Catholic Marriage Intended for College Classes (1946).

Husslein included four religious novels: Marie Buehrle, Out of Many Waters (1947); Alice Curtayne, “House of Cards” (1939); Arthur McGratty, Face to the Sun (1942); and Helene Margaret, Who Walk in Pride (1945).

In the miscellaneous category are the influential works of the Rural Parish Worker Movement: Luigi Ligutti and John Rawe, Rural Roads to Security: America's Third Struggle for Freedom (1940); Albert Muntsch, Cultural Anthropology (1934-36); Herbert Thurston, The Church and Spiritualism (1933). Helen Eden's Whistles of Silver and Other Stories (1933), a collection of medieval stories, was reviewed by The New York Times:

Mrs. Eden has the pen of a poet, the finish of a scholar, and she is acquainted with the magic of words. . . . A sparkling contribution to literature alike of priest and layman.32

According to The Saturday Review of Literature:

For those whose taste demands something delicate and lots of it, “Whistles of Silver” will provide a feast. A feast, too, served up in admirable style, with side-dishes elegant and appetizing.33

Also in the miscellaneous group would be two works on religion and culture: John Bannon, Epitome of Western Civilization (1942), and Ross Hoffman, Tradition and Progress, and Other Historical Essays in Culture, Religion, and Politics (1938).

Husslein began this work at the age of 58 and continued it during his 60s and 70s. Five of the books in “A University in Print” were written by Husslein.

Husslein published The Christian Social Manifesto: An Interpretative Study of the Encyclicals Rerum Novarum and Quadragesimo Anno of Pope Leo XIII and Pope Pius XI in 1931. This book systematically examined Rerum novarum as supplemented by Quadragesimo anno. Described as one of the best books of Catholic sociology of the period, it gave the definitive American treatment of Quadragesimo Anno. Husslein based this book on radio broadcasts he had made on Catholic social teaching. A reviewer wrote:

These encyclicals of Leo XIII and Pius XI Dr. Husslein submits to a masterly study in his book. He points out with great clearness the solution of the vexing problem as offered by the Catholic school of economic thought. Every situation is met in a practical way and every difficulty is answered.34

In 1934 Husslein published The Spirit World About Us. This work provided a biblically-based defense of angels, guardian angels, archangels, and spirits, defending the existence of the spiritual world against attacks from rationalistic and materialistic thinkers. Husslein attacked materialism because he saw it as the ultimate cause of social problems, since social injustice sprang from the failure to recognize transcendent moral principles.

For Heroines of Christ, published in 1940, Husslein edited a collection of stories on fourteen women saints such as Joan of Arc and Thérèse of Lisieux who had been either beatified or canonized in the previous ten years. This book presented these new heroines of the Church as models for women and as alternatives to the “new woman” described by socialists and radical feminists.

In 1940-1942 Husslein published the two-volume Social Wellsprings. Volume I consisted of fourteen documents of Leo XIII on social issues, each with a short commentary by Husslein. Volume II presented eighteen encyclicals of Pius XI on Social Reconstruction. Husslein believed it critical to provide readable translations of papal social writings.

n 1945 Husslein published The Golden Years: A Story of the Holy Family, by a Wife, Mother, and Apostle of Christian Charity and Joseph Husslein, S.J., Ph. D., Coauthor and Editor. This book was originally a spiritual journal written by a woman from a prominent American literary family. Husslein never identified the woman. Husslein reworked the journal and added several chapters.

Also in 1945 a controversy developed over the publication of A Padre Views South America. The book “was severely criticized by certain persons in Rome.”35 Father Husslein wrote a three-page defense of the work, claiming that the critics had not even read the book.

III. EvaluationHundreds of reviews were made of Husslein's books. More than eighteen books were reviewed by The New York Times; several were reviewed in The [London] Times Literary Supplement and The Dublin Review. Series books were reviewed in Time, The New Yorker, and frequently in academic journals in history, economics, sociology, philosophy, and psychology. Of course, the books were reviewed extensively by Catholic journals and magazines such as Commonweal, The Catholic Historical Review, and America. The majority of Husslein's books were given serious consideration when they were published. Five or more reviews for a book were not uncommon. Very few books were not reviewed at all.

The vast majority of the reviews of Husslein's books were positive. This was due in part to Husslein's selection of books but also due to the market of the books. Catholic journals were sympathetic to Husslein's project. The books reviewed by secular journals tended to be those that stood out, attracting the secular press. Only a few books were criticized as being too apologetical.

The Menace of the Herd by Francis Stuart Campbell received the harshest and most varied reviews. The American Sociological Review stated:

These three-hundred pages of intellectual muddles, logical contradiction, historical distortion, and sheer misrepresentation of contemporary fact defy summarization and detailed criticism.36

The Political Science Quarterly gave an equally blunt review:

The author is a man of many opinions--all of them avowedly conservative, monarchist, Catholic and antidemocratic. He does not like democracy and, with a great show of learning, he is anxious to explain the grounds of his distemper. He displays a grotesque ability to bend facts to his will.37

Yet a review in The Annals of the American Academy had this to say:

On the whole, this is a highly readable book, that should be read precisely because of the sting and spur it puts into the flank of democracy. Democracy, to use the Socratic simile, is a very big and strong horse which, just because of its strength and bigness, tends to become lazy.38

According to William Barnaby Faherty, the best-selling book in “A University in Print” was The New Testament by James Kleist and Joseph Lilly. The most influential books were Christian Life and Worship by Gerald Ellard and Husslein's The Christian Social Manifesto. Theodore Maynard's Queen Elizabeth and Henry the Eighth received high praise in the secular press.39

William Holub, President of the Catholic Press Association, gave this evaluation of Husslein's work:

The average Catholic's interpretation of the purpose of a university is essentially different from that which was prevalent several decades ago; the contribution of Catholic letters to the treasury of the world's great literature is being recognized today; social service is being stressed in the United States as a study important to cultural and economic progress. These accomplishments are traceable, in various degrees to the activities of Father Husslein.40

This assessment by Holub may be a bit exaggerated. George Higgins suggested “none of his books will be required reading a generation hence, but all of them are characterized by solid scholarship.”41 That only a few of these books would be read sixty years later is not surprising. That is the lot of the vast majority of all books. Husslein shared the fate of most publishers: some of his books did well; some did not, and a few books deserved more recognition than they received.

As one looks at the individual books in “A University in Print,” a few seem dated or overly enthusiastic in their Catholicism, but only a few. Even today, none of the books published seem embarrassing or silly. The thing that makes some of these books, especially the devotional works, seem dated is that they were written for their time. Their very timeliness in the 1930's or 1940's guarantees their lack of appeal sixty or more years later. As for the high-quality books, most were simply superseded in later generations with equal, better, or more up-to-date books.

Husslein described an effort of over twenty years with “A University in Print”:

This was my contribution to the Catholic Literary Revival throughout the world. It consists of a series of original volumes, written at my request or voluntarily submitted by competent literary men or authorities in their various fields, thus carrying on the Catholic tradition in letters and in the various scientific and cultural areas. Its object is to present to the world this tradition in its best and highest modern interpretation.42

NOTES

- *Dr. Werner is an adjunct professor at several universities in the St. Louis area. He teaches courses in Christian history, world religions, and mythology.

- 1Arnold Sparr, To Promote, Defend, and Redeem: The Catholic Literary Revival and the Cultural Transformation of American Catholicism, 1920-1960 (Westport, Connecticut, 1990). See also Dolores Elise Brien, “The Catholic Revival Revisited,” Commonweal, 106 (December 21, 1979), 714-716.

- 2Husslein's life is described in Stephen A. Werner, Prophet of the Christian Social Manifesto: Joseph Husslein, S.J., His Life, Work, & Social Thought (Milwaukee, 2001), and “The Life, Social Thought, and Work of Joseph Caspar Husslein, S.J.” (Ph.D. dissertation, Saint Louis University, 1990).

- 3Joseph Husslein, The Church and Social Problems (New York: America, 1912); The World Problem: Capital, Labor and the Church (New York: P. J. Kenedy, 1918); Democratic Industry (New York: P. J. Kenedy, 1919); Bible and Labor (New York: Macmillan, 1924); The Christian Social Manifesto (Milwaukee: Bruce, 1931).

- 4Descriptions of “A University in Print” can be found in Joseph Husslein, “A University in Print,” The Jesuit Bulletin, 15 (April, 1936), 1-3, 8; Joseph Husslein, “A University in Print,” The Jesuit Bulletin, 26 (February, 1947), 12-14; William Holubowicz, “A University in Print,” Sign, 21 (December, 1941), 281-282; William Barnaby Faherty, Better the Dream: St. Louis: University and Community, 1818-1968 (St. Louis, 1968), pp. 298-300, and Dream by the River: Two Centuries of Saint Louis Catholicism, 1766-1980 (St. Louis, 1973), p. 173.

- 5John A. O'Brien (ed.), Catholics and Scholarship: A Symposium on the Development of Scholars (Huntington, Indiana, 1939).

- 6Sparr, op. cit., p. 17.

- 7Husslein to the Father General [Wlodomir Ledochowski, S.J., Rome], February, 1938, Jesuit Archives, St. Louis, Missouri.

- 8Joseph Husslein, “Socialist Press Propaganda in the United States,” America, 4 (November 19, 1910), 128. See also his World Problem, pp. 169-170, and Church and Social Problems, pp. 201, 206.

- 9“Financing Socialist Literature,” America, 6 (February 3, 1912), 393.

- 10Husslein, World Problem, p. 169.

- 11Joseph Husslein, The Catholic's Work in the World (New York: Benziger, 1917), pp. 67-71, 95-106.

- 12Faherty, Better the Dream, p. 299.

- 13Cited in Husslein, “A University in Print,” Jesuit Bulletin, 15, 1.

- 14Ibid.

- 15Husslein, “A University in Print,” Jesuit Bulletin, 26, 12.

- 16Undated letter draft in Husslein correspondence files (1946) in Saint Louis University Archives.

- 17Joseph Husslein, preface to The Question and the Answer, by Hilaire Belloc (Milwaukee: Bruce, 1932), pp. ix-x.

- 18Husslein, “A University in Print,” Jesuit Bulletin, 26, 12.

- 19Husslein, “A University in Print,” Jesuit Bulletin, 15, 2.

- 20Saint Louis University press release, August 8, 1941, Jesuit Archives.

- 21Walter Romig (ed.), The Book of Catholic Authors: (First Series) (Grosse Pointe, Michigan, 1942), pp. 137-138.

- 22Betty Drury, review of From Dante to Jeanne d'Arc: Adventures in Medieval Life and Letters, by Katherine Bregy, in The New York Times Book Review, January 7, 1934, p. 19.

- 23Virgil Michel, review of Social Message of the New Testament, by Henry Schumacher, in Commonweal, 26 (May 21, 1937), 108.

- 24Review of The Catholic Eastern Churches and The Dissident Eastern Churches, by Donald Attwater, in The Dublin Review, 203 (December, 1939), 386.

- 25Charles F. Ronayne, review of Luther and His Work, by Joseph Clayton, in The New York Times Book Review, September 8, 1947, p. 9.

- 26Katherine Woods, “Hilaire Belloc on the 'True Crusade,'“ review of The Crusades: The World's Debate, by Hilaire Belloc, in The New York Times Book Review, June 13, 1937, p. 9.

- 27Review of The Oxford Movement, 1833-1933, by Shane Leslie, in America, 50 (December 30, 1933), 306.

- 28Review of The Greatest of the Borgias, by Margaret Routledge Yeo, in The Saturday Review of Literature, 14 (July 18, 1936), 21.

- 29“The Adam of Christendom,” review of Augustine's Quest of Wisdom: Life and Philosophy of the Bishop of Hippo by Vernon Bourke, in The [London] Times Literary Supplement, October 27, 1945, p. 415.

- 30Review of Religions of Unbelief, by André Bremond, in The Dublin Review, 206 (June, 1940), 384.

- 31Melvin J. Vincent, review of Facing Your Social Situation, by James F. Walsh, in Sociology and Social Research, 31 (September-October, 1946), 71.

- 32Laura Benet, “Helen Parry Eden's Stories and Poems,” review of Whistles of Silver and Other Stories, by Helen Eden, in The New York Times Book Review, August 6, 1933, p. 8.

- 33Aline Kilmer, “Delicate Erudition,” review of Whistles of Silver and Other Stories, by Helen Eden, in The Saturday Review of Literature, 10 (December 9, 1933), 334.

- 34Philip H. Burkett, S.J., review of The Christian Social Manifesto, by Joseph Husslein, in The Annals of the American Academy, 163 (1932), 242.

- 35Husslein to his provincial [Joseph P. Zuercher, S.J.], November 9, 1945, Jesuit Archives.

- 36Howard E. Jensen, review of The Menace of the Herd, by Francis Stuart Campbell, in American Sociological Review, 8 (August 1943), 482.

- 37.Robert K. Merton, review of The Menace of the Herd, by Francis Stuart Campbell, in Political Science Quarterly, 58 (December, 1943), 637.

- 38Wladimir Eliasberg, review of The Menace of the Herd, by Francis Stuart Campbell, in The Annals of the American Academy, 230 (November, 1943), 239.

- 39Faherty, Dream by the River, p. 299.

- 40Ibid., p. 300.

- 41George G. Higgins, “Joseph Caspar Husslein, S.J.: Pioneer Social Scholar,” Social Order, 3 (February, 1953), 53.

- 42Romig, op. cit., p. 137.