A Forgotten Dynamo: Daniel Lord, S.J.

(Originally published in AMERICAN CATHOLIC STUDIES Vol. 129, No. 2 (2018): 39-58. Reprinted with permission.)

Dan Lord had more impact on the day-to-day lives of ordinary Catholics during the early and middle parts of the 20th century than any other person, alive or dead.

William Barnaby Faherty, S.J. -- St. Louis Jesuit historian1

Daniel Lord, SJ, did an incredible amount of work. It has been estimated he wrote 20,000 words a month for publication for most of his career. His 228 pamphlets, covering every aspect of Catholic faith and life, sold over 25 million copies. He wrote thirty-two books, sixteen booklets, and seventy religious books for children. Part of Lord's success in getting into print was that he ran his own Queen's Work publishing operation. Lord also wrote seventy plays, musicals, and pageants, most of which he also produced.

Daniel Lord was a remarkable religious entrepreneur. As head of the Queen's Work office in St. Louis, he was always looking for new and innovate ways to reach his audience, whether it be pamphlets with catchy titles and cover graphics, musical pageants with casts of a thousand, lectures to high school and parish audiences, or his popular convention, the Summer School of Catholic Action. Lord was always experimenting. Furthermore, he raised the money for his efforts through the sale of his pamphlets and other materials. From 1926-1954 Daniel Lord traveled constantly across the country, often making four or more trips a month. He visited countless Catholic grade schools, high schools, colleges, and parishes and gave innumerable conferences, lectures, and retreats. In the process he met and interacted with more Catholics in the United States—students, lay adults, sisters, brothers, and priests—than perhaps anyone else. He also corresponded with tens of thousands of people. More than any other Figure, he had the pulse of Catholic America.

Yet sixty years after his death he is largely forgotten. Why? First, Lord intentionally did not write timeless literature. He always wrote for the moment to deal with a current question or problem and then moved on to his next project. Second, the most important writings of Lord are his pamphlets, few of which wound up in libraries. Third, Lord did not write for academics. In his own time most academics did not hold him in high esteem, even many of his fellow Jesuits.2Fourth, some dismissed Lord as a “popularizer.” Although Lord did write for ordinary people; with writing that is original, creative, and thought-provoking; his work is not light-weight. In his 1930 pamphlet, I Can Read Anything, for instance, he expects the reader to know Dumas, Hemingway, Ibsen, Noel Coward, and Bertrand Russell. This article urges a reconsideration of Daniel Lord and his career.

The Early Life and Career of Daniel Lord

Daniel Lord (1888-1956) grew up in Chicago and attended Holy Angels School.3 He subsequently attended St. Ignatius High School and College where he came under the influence of a Jesuit scholastic, Claude Pernin, who encouraged Lord's interest in literature, writing, and theater. Pernin was a demanding critic of Lord's writing. “He was indignant at mere imitation. He wanted the individuality of the writer to be written deep into the creation.”4 Lord wrote a western story that Pernin called “maudlin” and “mawkish”: “Frankly this thing reeks.”5 At St. Ignatius, Lord also played lead roles in school plays and started writing his own shows performed at his parish.

In 1909, Lord entered the Jesuits at St. Stanislaus Seminary outside of St. Louis for his novitiate. In 1913, at the end of his Juniorate, Lord went on a picnic, drank from a contaminated well, and caught typhoid fever. His recovery was slow, so he was pulled from his studies and sent to St. Louis to work with Father Edward F. Garesche, the new national head of the Sodality movement. Lord helped Garesche launch the magazine The Queen's Work and wrote articles and clever short stories for it. Lord later returned to his studies of philosophy and wrote a series of articles that were published in America and which became his first book: Armchair Philosophy.6

Between the fall of 1917 and the spring of 1920, Lord completed his Regency, teaching at the combined Saint Louis University high school and college. A dynamo, during these three years he started the university newspaper, helped restart the yearbook, organized the first student government, and created one of the first student fees to support campus activities. He also organized an orchestra and glee club and ran the newly formed SATC (Student Army Training Corps), an ROTC-type program on college campuses during WWI. Lord also set up a school of Saturday classes for Catholic teachers, mostly sisters and brothers. The classes had to be held off-campus since female students were not allowed at the university. In so doing, Lord broke the gender barrier at the university years before women were allowed as regular students. He also saw the need for education for Catholic sisters in the early growth years of the Catholic school system.

Between the fall of 1920 and the spring of 1924 Lord pursued his studies of theology in St. Louis. During that time, he started visiting Catholic institutions run by sisters in St. Louis and Chicago such as schools, orphanages, and institutes for the deaf. In light of those experiences, he wrote articles on his visits for The Queen's Work and America which would be combined into his 1924 book Our Nuns, a fascinating window into the world of Catholic sisters in the 1920s.

After his ordination in 1923, Lord went to Creighton University in the summer of 1924, where he, his Jesuit friend Louis Egan, and Sister Marie Anthony Haberl, brainstormed and wrote a proposal for a Catholic Art League to support Catholic artists. Lord wrote more plays and shows, including The Dreamer Awakes, a pageant about the missions performed by hundreds of school students as part of the Catholic Students Mission Crusade.7 In the summer of 1925, after his Tertianship, he went to Chicago to write a “Pageant of the Eucharistic” as part of the International Eucharistic Congress being planned for June 1926 by Cardinal George Mundelein. Lord designed a show with a cast of 1,250, which was ultimately rejected by the planners of the Congress.8

In 1925, Lord replaced Garesche as National Director of the Sodality in St. Louis. Sodalities were clubs at Catholic high schools, colleges, nursing schools, and parishes that sought to encourage religious faith among the laity.9 Eager to grow the movement, Lord built up subscription numbers for the Sodality magazine, The Queen's Work. He also started traveling extensively. He would go to a city and visit up to fifteen high schools and colleges during a school week, giving talks to faculty and students and inviting them to a two-day meeting that weekend to learn about setting up Sodalities. Lord also wrote a new manual, The ABC of Sodality Organization. The Queen's Work office likewise published numerous support publications for Sodalities, such as the Director's Service, Semester Outline, Parish Sodality Helps, a monthly Work Chart, and Sodalist Nurse. It also sent out liturgical material for discussion and study, guides for mental prayer, Catholic Evidence Guild outlines, poster suggestions, material for the Catholic Literature Committee, and posters announcing events such Vocation Week and Sodality conventions.10

Over the next two decades Lord traveled, lectured, and wrote to build up the Sodality movement to over 13,000 units. The Central Office suggested activities for local Sodalities but did not control them or tell them what to do. The Sodalities were designed to run themselves. His Sodality magazine, The Queen's Work, reached thousands with its blend of humorous comics, clever articles and short stories, comments on news items around the world, features on Sodality activities around the country, and interviews with famous Catholic movie stars. Lord also organized youth conferences at the national and local level which he called “Student Leadership Conferences” and worked to encourage parish sodalities for both men and women, each with their own conferences.

Looking back, Lord started working with young people and writing for them at a critical time in American history. The growing Catholic population needed more schools. As child labor laws and mandatory education laws became more common, many young people were freed from the need to work. A high school education became the norm and young people had more time for other activities. Lord thought that living out their Catholic faith could be one of those activities. As one account explained, “Father Lord found in the expanding American Catholic high school system a splendid opportunity for promoting religious life of the students through the sodality.”11

To further promote the Sodality movement and its reach and relevance, Lord started in 1931 the popular and influential Summer School of Catholic Action (SSCA), a week-long convention inspired by Catholic Action. In his 1933 pamphlet The Call to Catholic Action, he described the movement in these terms; “Catholic Action might, in consequence, be called twenty-four-hour-a-day religion. . . . Christ must be invited to dominate all the activities of humanity. He may not be reserved for the brief period of a Sunday's devotion or the swift flight of morning and evening prayer.12 Through Catholic Action, “Christ goes with the workmen to his bench and the stenographer to her typewriter; with the cook to her kitchen and the mother to her nursery; with the Catholic labor leader to his union meeting; with the Catholic farmer to his fields or his cooperative society; with the aviator to his plane, the seamen to a ship, the operator to his radio station, the officer to his regiment.”13

Even though he was a champion of Catholic Action, at times Lord also expressed his frustration that the term 'Catholic Action' had no agreed-upon meaning. He noted, “Few phrases have ever given rise to more magnificent achievements, more vagueness of mind, and more windy speech-making than the beautiful phrase, Catholic Action.” At the time a number of Catholic thinkers had very different ideas about Catholic Action running the gamut from radical social change to giving more support to the priest in the parish. For Lord, Catholic Action meant in part lay people taking the message of Christ and the church into the world. Lord also noted, “I have heard fervid orators, lay and ecclesiastical, haranguing the multitude to Catholic Action and sending them forth without the slightest idea of what they were supposed to do or how or why they were supposed to do it.”14

In numerous Sodality conferences, much attention was given to developing a more active Catholicism that went beyond personal devotion and attending liturgy. Over the years, discussion topics would include consumer cooperatives, mental prayer, the mystical body and social relations, Catholic literature, liturgy, teaching catechism in grammar school, college comedy, rural sodalities, Catholic propaganda, plays and drama, programs for democracy, musical games and recreational life, parliamentary law, school and sodality publications, and voting.15 Notably, Catholic sisters played a large and critical role in the SSCA. Group photos of SSCAs show priests in the front as a minority in a sea of sisters and lay people. These conferences provided unique opportunities for sisters, priests, and lay people to interact as equals and as partners. At many Catholic parishes there might be several priests and enough sisters to teach the entire grade school yet often they had little personal contact. At the SSCA everyone—men and women, clergy, religious, and lay—were equal workers in the vineyard. Lord's vision did not leave leadership and action to the priests alone. Indeed, the SSCA and the various conferences played an important role in helping Sodality members across the country feel part of something bigger—the larger Sodality community.

Appearing regularly at these conferences, Lord himself was often the main attraction as he lectured, typically with a chalk board. In the evenings he played piano for the sing-a-longs. Warm, funny, entertaining, and inspiring, Lord made religion interesting and challenging. His energy and excitement made young people want to get involved. In 1932, Lord wrote the song “For Christ the King,” also known as “An Army of Youth,” for Sodality youth conventions:

An army of youth

Flying the standards of Truth,

We're fighting for Christ, the Lord.

Heads lifted high,

Catholic Action our cry,

And the Cross our only sword.16

Decades later, people who learned the song at conferences can still sing the song with gusto. The Summer Schools with the slogan “Six days you'll never forget!” would last until 1968, by which time over 300,000 people had attended the SSCA and the other Sodality conferences.

Books, Booklets, and Pamphlets

In addition to his work with the Sodality movement, Daniel Lord was a prolific writer. He is remembered for devotional books, including His Passion Forever (1951) and Song of the Rosary (1953), and his work on Religion and Leadership, first published in 1931, became a popular college textbook for freshmen religion that was used well into the 1950s. Lord also wrote several short novels, including Murder in the Sacristy (1940), Clouds Cover the Campus (1942), and Red Arrows in the Night (1943), and published three collections of stories he had heard over the years: That Made Me Smile (1941), People You'll Like to Meet (1943), and These Tales are True (1948). He also authored a number of autobiographical works: Hi, Gang! (1941), a collection of charming stories about his youth, My Mother (1934), a tribute to his mother Iva Jane that give details of Lord's own life, and Played by Ear (1955), his own autobiography.17

Daniel Lord's most important writings, however, were his pamphlets. These works are easy to dismiss because they are, after all, just pamphlets. However, Lord wrote 228 of them covering the entire scope of Catholic faith and life—everything from the sacraments, to marriage and divorce, to naming a child and child safety. Lord's pamphlets provide a window into the many issues that were current in the Catholic world of the time. He produced a comprehensive body of literature in small, readable, and entertaining pamphlets to guide and teach Catholics.

His main market for selling pamphlets was the hundreds of thousands of Sodality members, especially young Sodalists, around the country. The Queen's Work office sold pamphlet racks that were put in schools and parishes and often maintained by Sodalists. During World War II pamphlet racks were even found on Navy ships. In part, Lord was motivated by the success of the E. Halderman-Julius Publishing Company of Girard, Kansas, publisher of Little Blue Books that initially sold for five cents a copy. The effort ran from 1919-1978 and sold over 300 million copies. The topics of the books covered philosophy and literature, but also salacious subjects such as The Love Affair of a Priest and a Nun, Curious and Unusual Love Affairs, and anti-religious subjects such as 61 Reasons for Doubting the Bible and Why I Reject the Idea of God.18

Lord's pamphlet writing began in earnest in 1927 and lasted until the last months of his life. Each year he created a Christmas pamphlet with a colorful cover such as For Us the Christmas Joy (1936); Christmas with Mary (1947); and A Star, a Child, and a Stable (1948). He also wrote fourteen novena pamphlets and some seventeen devotional pamphlets that were also catechetical such as I Don't Like Lent! (1937), The Man the Savior Praised: St. John the Baptist (1943), and Our Lady's Assumption (1934). His work on the sacraments included Confession is a Joy? (1933), The Sacrament of Catholic Action: Confirmation (1936), Attention, Godparents! (1951), and That Wonderful Sunday Mass (1955).

While his writing remained thoughtful and intelligent, Lord wrote his pamphlets in an engaging style and created characters similar to his readers. Some two dozen of his pamphlets included the fictitious character of Father Hall who lived at Lakeside Resort. During the summer he was visited by twins Dick and Sue Bradley, two college-age Catholics. In their conversations they discussed moral issues facing young people in pamphlets such as The Pure of Heart (1928), Don't Say it! (1929) on gossip, Speaking of Birth Control (1930), and Why Leave Home? (1931). In his autobiography, Played by Ear, Lord commented on the two characters,

Time and again I have been asked if Dick and Sue, the Bradley twins who figure in many of the “conversational” pamphlets, are real. In a sense they are. I wrote The Pure in Heart because parents of whom I was very fond wrote me about the problem of explaining sex to their growing children. Visualizing the boy and girl whom I knew and loved, I wrote the booklet. But from that time on, Dick and Sue were likely to be the last interested teenagers who asked me a vital question. Often I have replied to youthful questioners and reviewers: “Dick and Sue might turn out to be you, if you happen to ask me a particularly interesting and timely question.” .... They were intelligent, alert, attractive (or so I hoped), of good middle-class environment, with the normal problems, the constant interferences and distractions of modern life. . . .19

Lord's efforts to address timely matters can be seen in his writing on dating, marriage, and relationships. Among his pamphlets were What To Do on a Date (1939), Why Be a Wallflower? (1940), Going Steady (1941), and So We Abolished the Chaperone (1941), as well as some eighteen pamphlets on marriage such as Romance Is Where You Find It (1947),Is Love All That Matters? (1948), In-Laws Aren't Funny (1948), The Man of Your Choice (1952), and The Girl Worth Choosing: For the Boy Who Chooses and the Girl Who Wants to be Chosen (1953). Although the title So We Abolished the Chaperone seems quaint, this pamphlet still has relevance today as Lord criticized the attitudes held by many young men. These included ideas such as:

It's up to the girl. If she wants to be good and is willing to struggle for her goodness, I suppose I'll have to comply with her wishes. If she lets me get away with murder, then it's her responsibility.

Every young man should find out as soon as possible how much a girl will let him get away with.

If a girl says no, pretend that she has said yes. No doesn't mean no unless it is accompanied by a persistent and vigorous struggle.20

In essence, Lord was decrying what today is called “date rape.”

Considering Lord's pamphlets on marriage and family, along with his five books and booklets on the subject, he produced an important body of writing on the topic. Notable works include M Is for Marriage (1950), which practical advice on five important issues in marriage— Mind, Money, Manners, Meals, and Morals—and he explored problem of finances in his Money Runs or Ruins the Family (1942). Lord also wrote two pamphlets on divorce: Divorce: A Picture from the Headlines(1942) and About Divorce (1946). Lord's writings on marriage were important because they influenced Edward Dowling, SJ on Lord's staff who worked to create Cana Conferences to better prepare young people for marriage.

As might be expected, some of what he wrote is dated; for example, some of his arguments against birth control are no longer held. However, the bulk of what he wrote is straightforward and practical advice, still relevant today. In particular, Lord offered sound wisdom on the difference between romance and love, and practical guidance such as looking at a potential spouse's family and how he or she interacts with them.

Lord also wrote a number of pamphlets of general guidance on living life, including How to Pick a Successful Career (1935), A Guide to Fortune Telling (1939), I Can Take It or Leave It Alone (1939) on drinking, Are You a Weil-Balanced Person? (1948), Your New Leisure and How to Use It (1950), and Diet Can Be Fun (1952). In others, Lord's provided a religious interpretation of current events: God and the Depression (1932), It's Christ or War (1934), A Cure for Headline Jitters (1941), and Dare We Hate Jews? (1939) in which Lord spoke out against anti-Semitism. He wrote, “I frankly gag at any Christian's demand that I hate anyone—much more that I hate any race of people.”21 In all these works, he sought to provide a moral lesson. His 1929 pamphlet Fashionable Sin: A Modern Discussion of an Unpopular Subject, for instance, which sold over 125,000 copies, describes the world that has made immorality acceptable:

But your modern robber baron steals and cheats on a magnificent scale, bribes judges and tricks justice in the process, is ruthless toward weak competitors, turns his inner office into a seraglio, and then hires some psychologist to tell him that he is a superman, following his atavistic instincts and gets a philosopher to assure him that since there is no God he may make his own commandments and conveniently break them when he chooses.

When a woman of other days betrayed her husband, she admitted herself to be an adulteress. An impure woman might shrink from the brutal names hurled at her, but she admitted their sad truth. Your modern heroine thinks no more of a week end of adultery than she does of a week end of golf; and far from betraying her husband, she is probably acting with his consent and cooperation. As for the impure woman, she is rapidly being abolished in favor of the girl who lives up to the impulses of her artistic and emotional nature.22

In effect, Lord's pamphlets served as a kind of catechism. Through them, Lord wanted to educate Catholics, particularly young Catholics, in their faith. Knowing that many young people did not read much, he created pamphlets that could be read in about an hour. He used catchy titles and cover graphics to entice someone to pick up a pamphlet, look at it, and then buy it. He avoided titles that a young person would be embarrassed to be seen reading in public, such as on a bus or streetcar.

Among his most important works, several dealt with the sacraments and spiritual life, including his best-selling work, Confession is a Joy? (1933), which had 36 printings and sold 340,000 units, and Prayers are Always Answered (1927), which had 33 printings and sold 294,000 units. He also wrote several pamphlets on the importance of Catholic education: Murder in the Classroom (1931) and The Magnificent Catholic College (1954). In the former, Lord spoke eloquently about the church's teaching, explaining that

We must not forget that Catholicity is not merely an external form; it is a system of life and living. It is a historic tradition 2000 years old. It is faith permeating knowledge and supported by the cold, clear reasonings of philosophy and science. It is art and music and beauty and literature and drama all in one magnificent unity. It is big enough to take in the latest findings of science and yet to remember the undying words of Christ; to be interested in the last discoveries in Egypt without forgetting the God who is ages older than the pyramids; to be ever as modern as the day and as enduringly ancient as the rock of Peter.23

Another two dozen pamphlets fall in the category of apologetics. Some are about religious faith such as Christ the Modern (1932), Atheism Doesn't Make Sense (1936), Faith Is a Chain (1939), Man Says “If I Were God . . .”(1940), What Catholics Think of Christ (1948), and What Catholics Think of the Church (1948). Other pamphlets defend the Catholic Church: The Church Is Out of Date? (1935), The Priest Talked Money (1939), St. Peter: Pope or Impostor? (1947), and The Church Can't Order Me! (1954). In The Church Is A Failure? (1939) Lord wrote:

The Church is not an ethical-culture society conducting classes in abstract truths or aesthetic entertainment. It's a tough organization demanding a lot of hard things for its members.24 The Church bravely and with sublime and often apparently unfounded optimism goes on making terribly difficult demands. After nineteen hundred years of pretty bitter and disillusioning experience the Church holds to her unfaltering belief in humanity.25

Lord wrote these pamphlets to teach Catholics how to defend their faith. Readers could also pass on the pamphlets to friends or co-workers who were critical of the Catholic Church.

Yet more than an apologist, Lord also served as a champion for Catholicism, as can be seen in his substantial writings on the subject of vocations. In The Chance of a Lifetime (1946), one of Lord's more important pamphlets on the topic, for instance, he takes the call for priesthood and the religious life to a whole new level. Not just one more pamphlet on vocations, it was Lord's bold vision for the future.

This booklet is being written in the year 1945. The war—in Europe and in the Pacific—will soon be receding memory. So some of the heroes and heroines who have done so much to demonstrate the courage and virtue of America may pick this booklet up, page through it curiously, and find—is it too much to ask?—that God is offering them a chance in a lifetime.26

Lord notes that sometimes people who enter the sanctuary or convent are accused of cowardice for trying to escape the real world. “Plausible as it may sound, it turns out to be the most arrant nonsense.”27 Lord offers his “Tough Invitation”: “I should want fighting men and women prepared to enter the toughest battle the world can ever know, the struggle of God against evil, of right against wrong, of the powers of light against the powers of darkness.”28

Altogether, Lord wrote six pamphlets on vocations including: Shall I Be a Nun? (1927), Shall My Daughter Be a Nun? (1927), The Call of Christ: A Study of Religious Vocation for Young Men (1927), and Spinsters Are Wonderful People: In Praise of Unmarried Women (1947) on the single life for women. Lord's writings about Catholic sisters were particularly important since he wrote at a time when the rapidly growing Catholic school system created a huge demand for sisters to staff them.29 There is no way to know or measure the impact of Daniel Lord on countless young women and men considering vocations to the religious life. He interacted with many at the conventions. He wrote numerous personal letters most of which have not survived. In fact he often considered letter writing to be his First Apostolate: possibly, he wrote more than 100,000 personal letters. Very likely Lord influenced hundreds of young people to enter the convent or seminary. He even admitted that some fathers had threatened to kill him for encouraging their daughters to become nuns. Lord also wrote his book Letters to a Nun in 1947 giving guidance and advice on leading the religious life. Lord's colleague Edward Dowling, SJ, would state: “The greatest thing Father Lord ever did was to discover the American nun.”30

Although the bulk of his pamphlets are worth reading today, a few are dated. Lord's attitudes against religiously-mixed marriages seem a bit harsh to modern readers. In fact his 1936 pamphlet Forever and Forever gives an unnerving description of eternal damnation for a man who married a divorced non-Catholic women. In a few pamphlets, when talking about Protestant churches, Lord lacks the more respectful attitude that would emerge with the ecumenical movement in the 1950s and the Vatican II document Unitatis Redintegratio. Typical of many Catholics of his time, Lord had a romanticized and uncritical view of the Crusades. His view of contemporary world affairs could also be clouded. In two pamphlets What's the Matter With Europe (1937) and The Pope in the World Today (1938) Lord supported Pope Pius XI in not taking a stronger stance against Mussolini and Hitler, seeing Communism as a bigger threat. In holding that view, Lord was typical of many Catholics of the time who trusted that the Pope knew what he was doing.

These are the main flaws that can be found in Lord's writings, but they should not be used to judge the rest of his writing as being out-of- date or superficial as they represent only a small part of his writing. The majority of his writing is insightful and relevant today. Lord described a lived-out-daily spirituality that modern readers can understand. He made religious faith accessible and he wrote with a humor and charm that are still engaging some seventy years later. Lord's pamphlets are being made available online where they can be read anew and contemporary readers can make their own assessments.31

Lord's Later Career and Final Days

In May 1943, the Jesuit Provincials in America named Daniel Lord as the National Director of the Institute of Social Order, the ISO. As one of Lord's biographers noted, “the Institute, however, took off like a Roman candle, lit up the sky brilliantly but briefly and fell back to earth in ashes.”32 The ISO was an ambitious plan to embrace Catholic teaching about social justice then educate Jesuits about social justice who would in turn educate the broader Catholic population. The ISO would involve both research and dissemination, and to that end Lord created committees on Interracial Justice, Labor Relations, Pan- Americanism, Peace Terms and Conditions, Recreation, Social Legislation, and Democratic Activities.

As part of his work with the ISO, Lord created the thirty-two page ISO Bulletin for his fellow Jesuits. The Bulletin, which encouraged a free exchange of opinions, aimed at educating Jesuits on Catholic social teaching and its application and engaging them in discussion. Lord included articles and letters from Jesuits expressing a wide range of opinions including letters that were critical of the efforts of the Jesuits and the church. Lord wanted interesting articles even if not written by experts. As Thomas Gavin notes, “probably no Jesuit publication in the 20th century was so eagerly read and discussed by so many Jesuits. ... It was promptly penalized for its hospitality to writers who dared to challenge certain accepted views.”33

Lord's free exchange did not go over well with the Provincials. His superiors also did not like the publication of articles by non-experts, and Lord was eventually removed as head of the ISO. The last issue of the ISO Bulletin would be April 1947, replaced by Social Order, edited by the new director, Leo Brown, SJ. The new publication had longer, more academic articles and was far less interesting. Brown would head the research Social Order Institute which continued for many years.

Lord headed the Sodality movement until the late 1940s when he was pushed out by Jesuits on his staff who thought Sodalities should focus on a select few members who would receive intense spiritual training. Lord believed Sodalities should be open to all who were interested and should include a broad range of activities. Lord lost the fight for control of the vision. The bigger loser was the Sodality movement, which began a steady decline. One surviving part would join with the Christian Life Community movement. By the late 1960s most school sodalities and many parish sodalities would be gone.34

His publication efforts, however, still thrived. Queen's Work publishing, which Lord had established, continued to produce the monthly The Queen's Work magazine into the late 1960s. In addition, Queen's Work publishing, with its own print shops, would produce most of Lord's 228 pamphlets and dozens of his books, booklets, and plays, as well as works by many other authors, many of whom were Jesuits. By 1949, when Lord was removed as head, Queen's Work had published over eighty-five pamphlets and books by other authors. From 1950 to 1963, another 150 pamphlets and books by others would be published. In 1963, Liguori Publishing bought the existing inventories and continued to sell over 280 of these pamphlets, books, booklets, leaflets, and catechetical materials. Queen's Work publishing, during its years of existence, was a significant Catholic operation producing Catholic literature.

In his last years, Lord wrote and produced several musical pageants. For his 1949 show Salute to Canada, about the North American Jesuit Martyrs, Lord used a professional twenty-four piece orchestra conducted by Harold Sumberg from the Toronto Symphony Orchestra. The show included the Volkoff Canadian Ballet with Boris Volkoff. The show had three scenes with two intermissions on an outdoor stage, 70 ft. wide and 50 ft. in depth, built into a hillside. 50,000 people saw the show with its cast of 750. Lord did two shows at the Jesuit-run University of Detroit: City of Freedom (1951) and Light Up the Land (1952). City of Freedom was seen by over 150,000 people. Light Up the Land was filmed by Ford Motor Company.35

In January 1954 Lord found out he had cancer. He kept active during the next months and wrote several books including his autobiography, Played by Ear. He also wrote a short piece, “The Verdict Was Cancer,” which would be published as My Good Angel of Death and was widely read.36 Despite his illness, he continued all his correspondence and wrote his “Along the Way” syndicated column. He had written one a week since 1933: some 1,050 columns! For over twenty years, countless Catholics across the country read them in diocesan newspapers. He produced his last show in the fall of 1954 in Toronto: The Marian Year Pageant. Due to the ravages of cancer, he had to direct the show from a cot. In his last days, Lord grew delirious and was prone to giving stage directions: “get going on this right away . . . step it up . . . hurry, hurry.” Daniel Lord, SJ, died on January 15, 1955.

Lord had a great influence on those around him. In 1954, Life magazine surveyed 7,500 Jesuits in the United States who voted Daniel Lord their most effective priest.37 He had a contagious vision that others caught. Among the many he influenced was Claude Heithaus, who worked under Lord at Saint Louis University to set up the university newspaper and yearbook. As a Jesuit priest, Heithaus later forced the university to desegregate. The Markoe brothers, John and William, fighters for racial justice in St. Louis, were among Lord's close friends.

Father Edward Dowling, SJ, who served on Lord's staff, “did conspicuous work through such organizations as Alcoholics Anonymous, the Cana Conference Movement, and 'Recovery Incorporated’ for nervous people. He became one of the most deeply revered priests of his generation and the only priest listed in the book Top Leadership U.S.A.”38 Dowling had a big influence on Bill Wilson, the founder of Alcoholics Anonymous. Queen's Work staffer Aloysius Heeg, SJ, created catechetic material that “made his name synonymous for a time with teaching religion to youngsters throughout the United States.”39 Father William Barnaby Faherty from Lord's staff became the eminent historian on St. Louis and its religious and Jesuit history. Lord likewise inspired many woman religious who caught his vision and began to push boundaries and become leaders in their communities such as Sister Mary Agnes Bosche at Notre Dame College in Cleveland and Sister Mary Daniel Coffey who helped found the Carmelite Monastery in Jackson, Mississippi where the chapel is dedicated to Daniel Lord and his bust can be seen at the main entrance.40

Several scholars have given their assessments of his life and work. Father Faherty, the St. Louis Jesuit historian, wrote how “Father Lord taught an entire generation that religion should permeate life with true joy in the possession of God. He brought optimism into the heart of American Catholic living.”41 David Endres, writing in 2005, described Daniel Lord as representing “a pioneering vision for the church's ministry in a modern, media-saturated world. Lord championed a form of public Catholicism meant to compel youth to take their faith out into the world, not to leave it sequestered in churches and schools, ‘safe’ from spreading. What appealed to a generation of Catholic youth and what should elicit our admiration today is Lord's zeal to communicate with people using the most effective means available, whether the stage, the written word or the cinema. Lord's works connected the faith with the experiences and interests of youth, employing modern technology and cultural themes without shortchanging the vitality of the church's teachings.”

Indeed, Lord's ability to engage and energize youth was unmatched in his time.42 In 1955, a Jesuit contemporary wrote:

He was called everything from a vulgarian to a mass hypnotist; he was charged with inventing “River Rouge assembly-line” spirituality, of catering to the more susceptible and gentler sex; he was berated as a Catholic “Billy Sunday,” and then as a “Billy” Graham; he was a “priestly Gable,” a clerical showman, a Midwestern Rotarian, a piano tinkler of the Basin Street school, a tinkling cymbal, commercial, crude, superficial. He was a simplist, “anti-intellectual.” He heard it or heard about it—and went on. He did what he could with what he had. And in the doing he showed so much love!

He, even more than Jean-Paul Sartre, believed in the importance of the here and now; the present moment was all he had, not to sin, but to serve God. Not a minute was to be wasted, and so he lugged his battered portable on the Pullmans from coast to coast and, in a generation, changed the whole aspect of American Catholicity from diluted Jansenism to joy.43

Daniel Lord's mission was to communicate with modern people and to energize them in their faith. His fresh and innovative approaches were rejected by traditionalists. He was a work horse always writing even as he traveled the country. Lord focused on the present. What at this moment can I write or say? What is the current topic of interest to Catholics, especially young Catholics? What new approach should I try to get their attention?

Conclusion: Speculative Questions

Over the past two decades I have worked through the Daniel Lord material. As I looked at all the different pieces of his immense body of work, it seemed likely that no other Catholic figure had done so much. This article has laid out much of what Lord did; but as a colleague said about him: “Every time you think you have a list of the things he does, you find out you've left out about half of them.”44 Clearly, Lord was one of the most influential American Catholic religious figures of his generation, especially considering his impact on ordinary Catholics.

How influential was he? How big was Daniel Lord? Admittedly, there is no way to measure influence or to come to agreement on who had more influence. Who would be on the list of most influential? Fulton Sheen reached millions with his radio and TV broadcasts. Charles Coughlin had a huge radio audience in the 1930s. The writings of Thomas Merton inspired and influenced many and continue to do so. The powerful Cardinal Spellman of New York had great influence. Dorothy Day had a great impact. What about the influence of Bishop John Carroll who did so much to shape how the Catholic Church would fit into American culture? How would one rank such figures in terms of influence? Who else should be included on the list? How does Daniel Lord compare? This is a speculative question for those interested in pondering it.

A more important question is why was Lord so successful and productive in communicating his message? Surely Lord's personality, energy, and imagination were key, but he was also the right person at the right time, given the technology of the 1920s through the 1950s. In an era of modern communication technology, a number of important lessons can still be gleaned from his work. First, Lord met, talked with, and corresponded with countless people, especially young people. He knew what they were thinking: their questions, problems, and stories. Lord knew his audience. Second, Lord was always trying new and different ways to reach out to his audience. He was always innovating and gathered a creative and imaginative staff around him. Third, until the late 1940s, he was in charge and did not have to work under stifling superiors. He could envision and carry out his plans. Fourth, Lord believed that Catholic teaching had much to teach about religious faith and how to live life. Lord believed in his message and wanted to share it by any means possible.

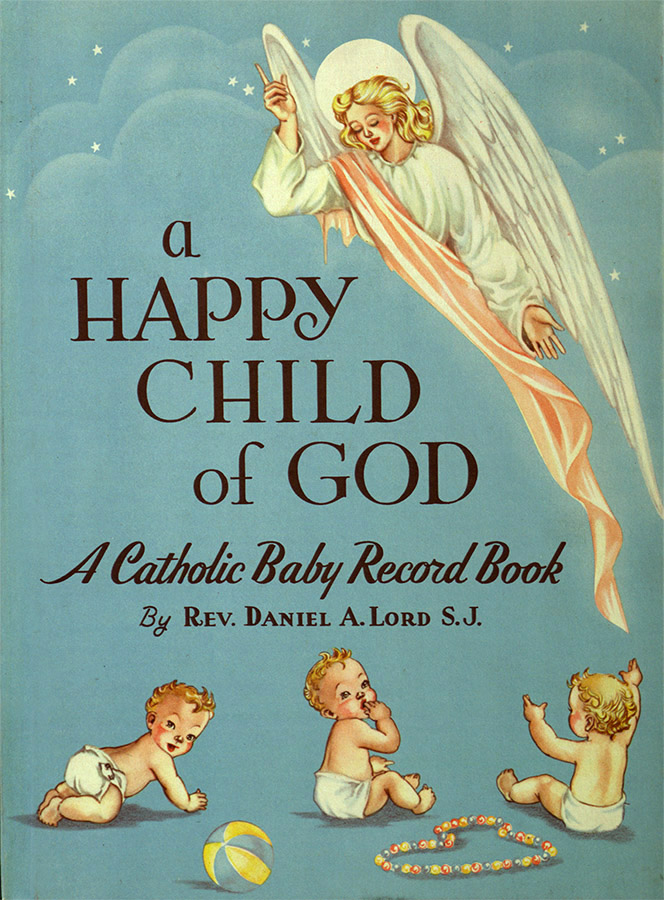

Lord’s Children’s Books

Daniel Lord as Technical Advisor for the 1926 Movie The Kings of Kings.

Notes

- 1William Barnaby Faherty, SJ, St. Louis Jesuit historian, as told to John Waide, archivist in St. Louis, interview, March 15, 2015.

- 2The one area of Lord's work that has received attention from academics is the 1930 Motion Picture Production Code written by Lord. See. for example, Gregory D. Black. The Catholic Crusade Against the Movies, 1940-1975 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998); John T. McGreevy, Catholicism and American Freedom: A History (New York: Norton, 2003), 156-157; and Stephen Vaughn, “Morality and Entertainment: The Origins of the Motion Picture Production Code,” The Journal of American History (June 1990): 39-65.

- 3The life of Daniel Lord is covered in three books he wrote: his autobiography Played By Ear (Chicago: Loyola University Press, 1956); My Mother (St. Louis: Queen's Work, 1934); and Hi, Gang! (St. Louis: Queen's Work, 1934). Two biographies exist: Thomas F. Gavin, SJ, Champion of Youth: A Dynamic Story of a Dynamic Man: Daniel A. Lord, S.J. (Boston: Daughters of St. Paul, 1977); and Joseph T. McGloin, SJ, Backstage Missionary: Father Dan Lord, S.J. (New York: Pageant Press, 1958). A recent tribute is David J. Endres, "Dan Lord, Hollywood Priest" America (December 12, 2005), 20-21. See also David J. Endres, "The Global Missionary Zeal of an American Apostle: The Early Works of Daniel A. Lord, 1922-1929," U.S. Catholic Historian: 24 (Summer 2006): 39—94; William Barnaby Faherty, Better the Dream, Saint Louis: University & Community, 1818-1968 (St. Louis: Saint Louis University, 1968); and "A Half-Century of the Queen's Work," Woodstock Letters, 92 (1963): 99-114.

- 4Daniel A. Lord, SJ, My Greatest Teacher (St. Louis: Queen's Work, 1947), 26.

- 5Ibid. See McGloin, Backstage Missionary , 34-36.

- 6Daniel A. Lord, SJ, Armchair Philosophy (New York: The America Press, 1918).

- 7See Endres, "Hollywood Priest," 41-42 on the origin of the CSMC. See also Angelyn Dries, The Missionary Movement in Catholic History (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1998). 87-92, and Endres, "Global Missionary Zeal."

- 8Lord. Played by Ear, 250. See Mary Kathryn Barmann, A.B., "A Report: The Contribution of Reverend Daniel A. Lord, S.J. to the Theater," Saint Louis University, MA Thesis, 1954, 157-159; Lord. The Jesuit with Magic Hands (St. Louis: Queen's Work, 1948), 48-50. For an overview of the Congress see Jay P. Dolan, The American Catholic Experience: A History from Colonial Times to the Present (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1985), 349-350.

- 9See William D. Dinges, “‘An Army of Youth': The Sodality Movement and the Practice of Apostolic Mission," U.S. Catholic Historian (Summer 2001): 35-49.

- 10Sister Mary Florence, S.L. (Bernice Wolff). The Sodality Movement in the United States (St. Louis: Queen's Work, 1939), 145-146.

- 11William Barnaby Faherty, Dream by the River: Two Centuries of Saint Louis Catholicism, 1766-1980 (Saint Louis: Piraeus, 1973), 159.

- 12Daniel A. Lord, SJ, The Call to Catholic Action (St. Louis: Queen's Work 1933), 23.

- 13Ibid., 29-30.

- 14Daniel A. Lord. SJ, "Schools of Catholic Action," Studies (September 1933), 454- 455.

- 15 Lord, “Schools of Catholic Action,” 454-467; “Sodalities in America and Catholic Action,” Studies (June 1933), 257-270.

- 16Daniel A. Lord, SJ, For Christ the King (St. Louis: Queen's Work, 1932).

- 17The prominent movie producer John Considine (famous for his 1938 film, Boys Town, starring Spencer Tracy) bought an option on My Mother, although the movie never happened.

- 18Gavin, Champion of Youth, 78.

- 19Lord, Played by Ear, 334.

- 20Daniel A. Lord, SJ, So We Abolished the Chaperone (St. Louis: Queen's Work, 1940), 21.

- 21Daniel A. Lord, SJ, Dare We Hate Jews? (St. Louis: Queen's Work, 1939), 9.

- 22Daniel A. Lord, SJ, Fashionable Sin (St. Louis: Queen's Work, 1929), 4.

- 23Daniel A. Lord, SJ, Murder in the Classroom: The Summer Colonists Discuss Catholic Education (St. Louis: Queen's Work, 1931), 23-24.

- 24Daniel A. Lord, SJ, The Church Is a Failure? (St. Louis: Queen's Work, 1939), 13.

- 25Ibid., 14.

- 26 Daniel A. Lord, SJ. The Chance of a Lifetime (St. Louis: Queen's Work, 1946), 4.

- 27Ibid., 11.

- 28Ibid.

- 29George C. Stewart, Marvels of Charity: History of American Sisters and Nuns (Huntington, IN: Our Sunday Visitor Publishing Division, 1994), 320-329.

- 30Gavin, Champion of Youth, 100.

- 31These webpages have a number of Lord's pamphlets: http://daniellordsj.org/Lord- Writings.html and http://cdm.slu.edu/cdm/landingpage/collection/lord. The digitization has been undertaken by the Pius XII Memorial Library, Archives and Digital Services at Saint Louis University.

- 32Gavin, Champion of Youth, 133. The Institute was started in 1939.

- 33Ibid., 136.

- 34Gavin, Champion of Youth, 164. The archival correspondence among the Jesuits of his staff for this period is in a file labeled, “Sodality Wars.”

- 35The film, Light Up the Land, can be viewed on the website of the University of Detroit Mercy Library Special Collections: http://research.udmercv.edu/find/special_collections/digital/light/.

- 36An interview of Lord discussing his cancer can also be found on YouTube as “So I’m Dying of Cancer. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=:i_vnyJowOSA.

- 37Gavin, Champion of Youth, 24, citing letter from James C. Lipscomb of Life magazine, January 29, 1954.

- 38Faherty, Dream by the River, 177.

- 39Ibid.

- 40Arntz, Sister Mary Luke, SND, Remembering Sister Mary Agnes: 1885-1949; website for the Carmelite Monastery of Jackson: https://www.jacksoncarmel.com/history.

- 41Faherty, Better the Dream, 358.

- 42Endres, “Dan Lord, Hollywood Priest,” 21.

- 43Alfred Barrett, SJ, “Father Lord - Citizen of Two Worlds,” Catholic World (March 1955), 402-421.

- 44McGloin, Backstage Missionary, 12.